JUNO AND JUPITER

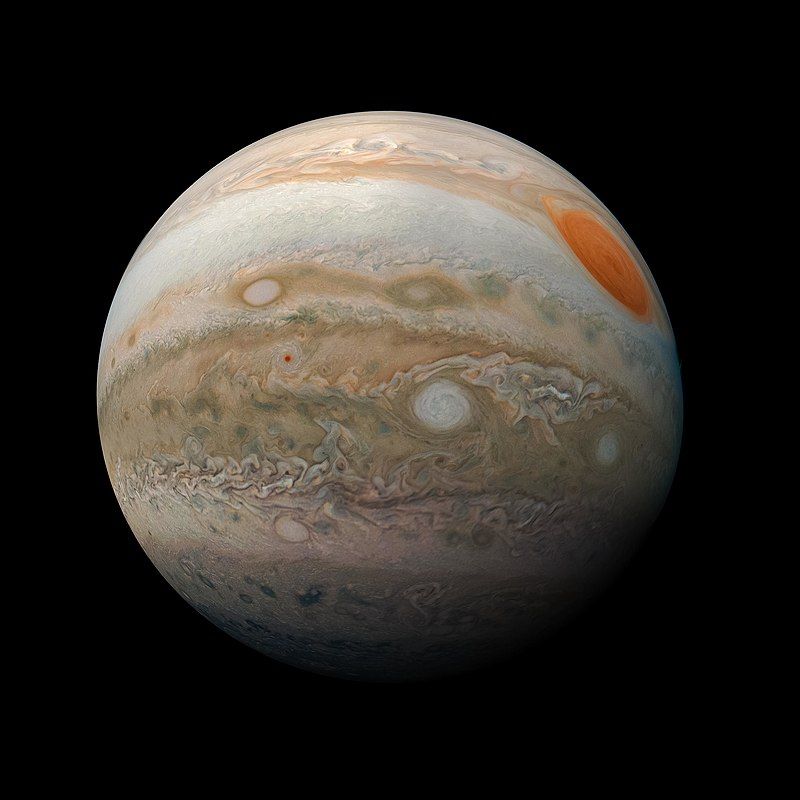

Out past the asteroid belt of the Solar System lives Jupiter, and recently it has been joined by the space probe Juno, courtesy of NASA. Built by Lockheed Martin and operated by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, this spacecraft launched on August 5, 2011, as part of the New Frontiers program. Juno reached Jupiter and entered its orbit on July 5, 2016, and began its scientific investigation of Jupiter.

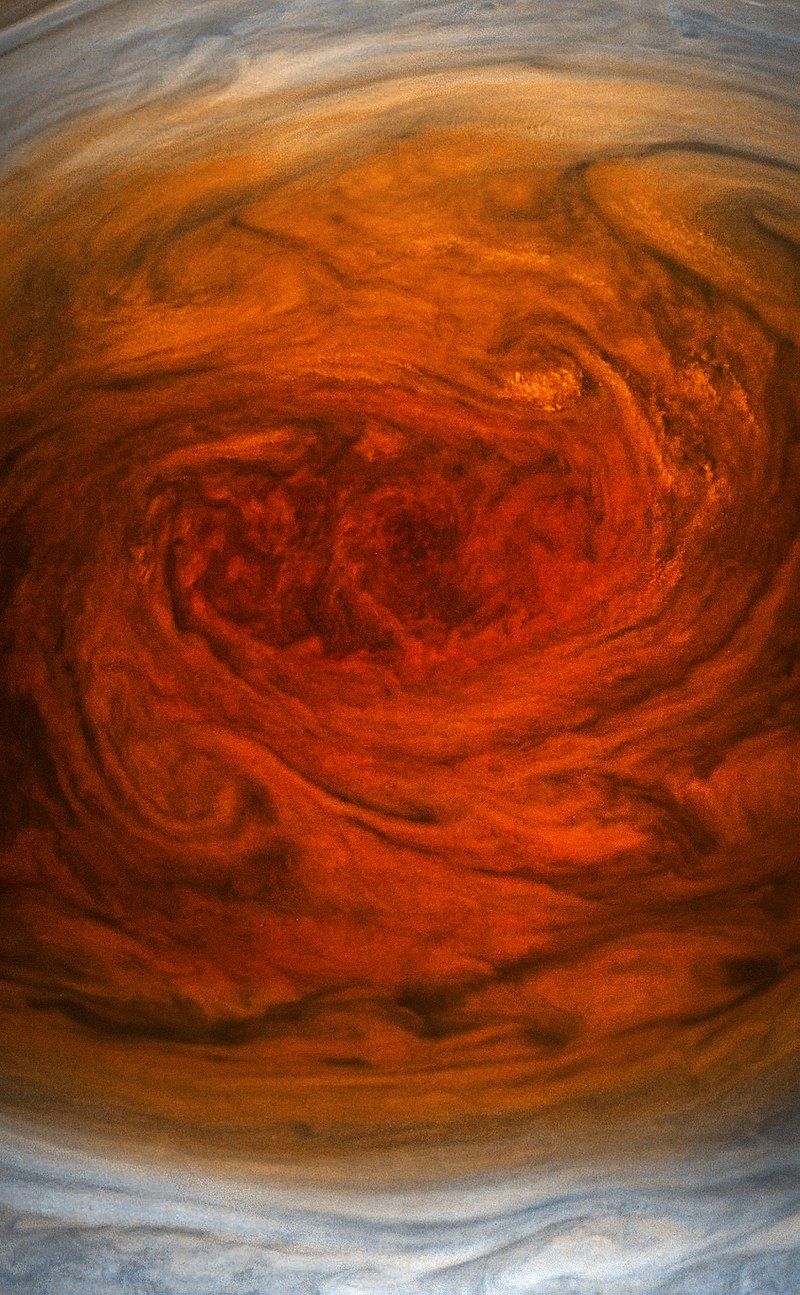

Juno's primary mission objective is to measure Jupiter's polar magnetosphere, composition, gravitational field, and magnetic field. Juno is also searching for clues to help us understand how Jupiter was formed, including the amount of water present in the atmosphere, if it has a rocky core, mass distribution, and deep winds, reaching up to 620 kilometers per hour (390 mph).

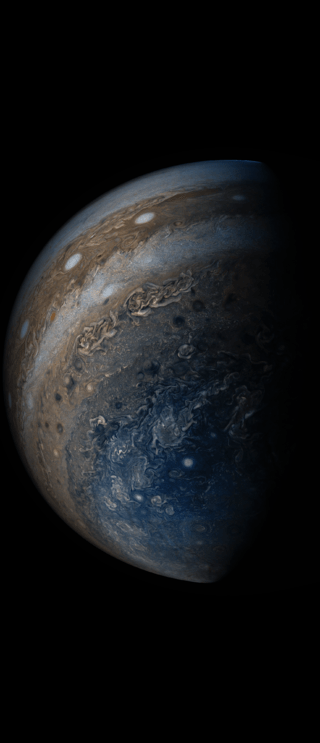

Juno is the second, only to the nuclear-powered orbiter Galileo, which orbited from 1995 to 2003, spacecraft to orbit Jupiter. Juno is powered by solar arrays, unlike all the earlier space crafts sent to the outer planets. Solar panels are commonly used by satellites orbiting Earth and working in the inner Solar System. Juno has the three largest solar array wings ever deployed on a planetary probe, and they play a key role in stabilizing the spacecraft as well as generating power.

While it has been out there observing, Juno has provided its first results on the amount of water in Jupiter's atmosphere! Juno estimates that about .25% of the molecules in Jupiter's atmosphere are made from water at the equator. This is the first finding concerning the abundance of water on Jupiter since the Galileo mission suggested that Jupiter might be extremely dry. This is an amazing discovery because an accurate estimate of the amount of water in Jupiter's atmosphere has been something scientists have been longing for. This is critical information that will help us understand how our solar system was formed. Jupiter was very likely to be the first planet, and it contains most of the gas and dust that wasn't sucked into the Sun.

The Juno mission was supposed to end in February 2018, and Juno was to be de-orbited after completing 37 orbits of Jupiter, but Juno was given an extension until July 30, 2021. When Juno reaches the end of its mission in 2021, it will perform a controlled de-orbit and disintegrate into Jupiter's atmosphere. This is to prevent any future failure of instruments and risk collision with Jupiter's moons after being exposed to high radiation levels from Jupiter's magnetosphere.