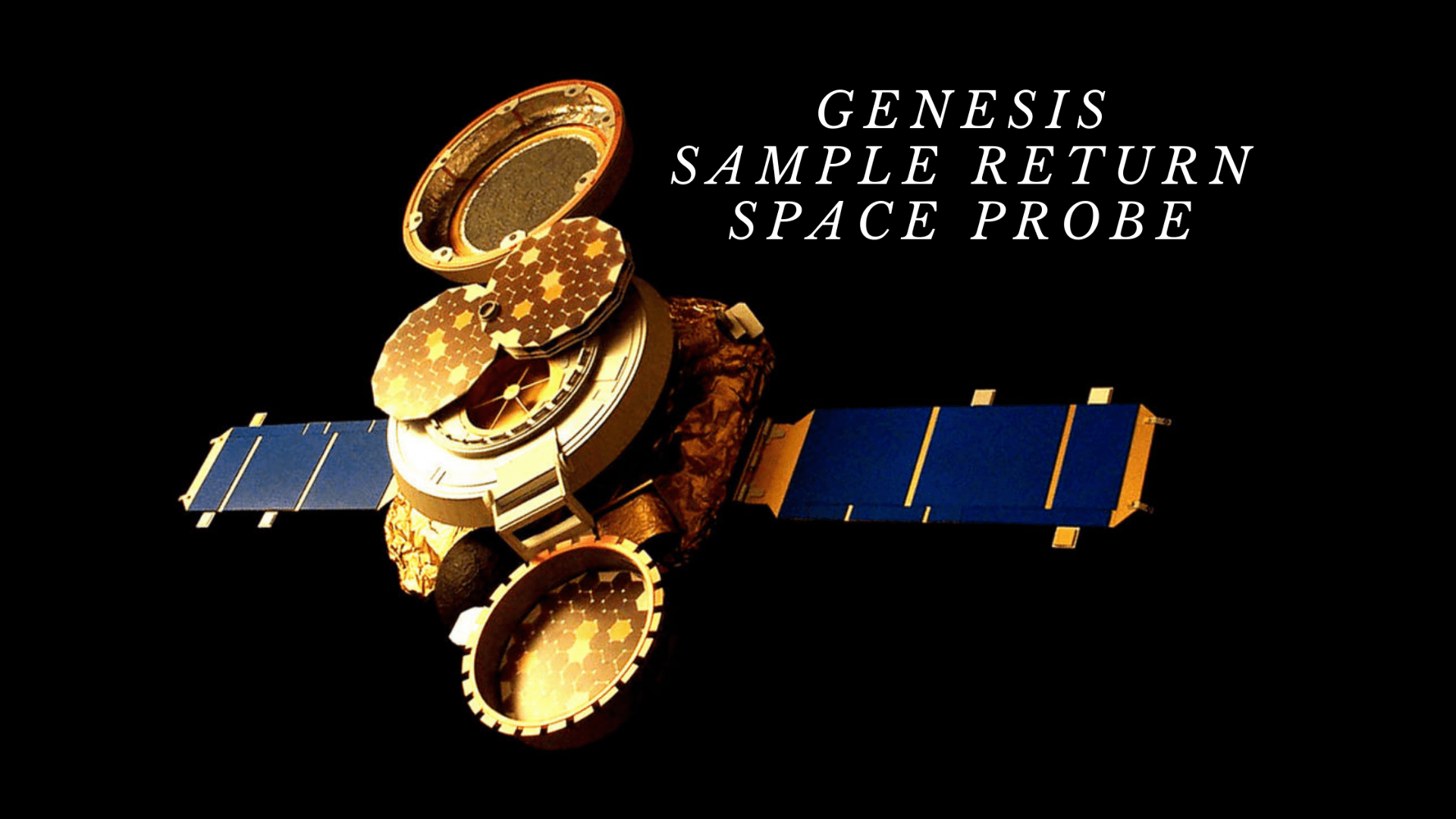

Genesis Space Probe

Genesis was a NASA sample-return space probe that collected and returned solar wind particles for analysis. It was the first NASA sample-return mission since the Apollo program to return material and the first to return material from beyond the Moon. Genesis launched on August 8, 2001, and exposed its collector arrays on December 3, 2001, and began collecting solar wind particles. After 850 days, the collection process ended, and Genesis began its return on April 22, 2004. The sample return capsule separated from the spacecraft on September 8, 2004, and returned to Earth for the planned recovery.

Extensive planning for the capsule's retrieval had been conducted: a normal parachute landing could damage the delicate samples, so a mid-air retrieval of the capsule was planned. A drogue parachute was to be deployed around 33 km (21 mi) above the ground to slow descent. Then, a large parafoil would be deployed around 6.7 km (4.2 mi) to slow descent further and keep the capsule in stable flight. A helicopter would then attempt to catch the capsule by its parachute on the end of a five-meter hook, and the capsule would be soft-landed once retrieved. However, the sample return capsule entered Earth's atmosphere over northern Oregon on September 8, 2004, at nearly 11.04 km/s (24,706 mph). The spacecraft's descent was slowed only by its air resistance due to a design flaw with the deceleration sensor. The planned retrieval could not occur as planned, and the capsule crash-landed into the desert floor at about 86 m/s (310 km/h; 190 mph) at the Dugway Proving Ground in Tooele County, Utah.

Initial investigations showed that some sample collection wafers had crumbled on impact, but others were intact, and although desert dirt entered the capsule, liquid water had not. Because the solar wind particles were embedded in the wafers, whereas the contaminating dirt was just lying on the surface, this made separating the sample from the contaminating dirt much easier. However, it was not terrestrial desert soil that proved most difficult to deal with during the sample analysis process. The craft's own compounds, such as lubricants and craft-building materials, proved more difficult to separate from samples in the aftermath of the crash. The analysis team believed they would be able to achieve most of their primary science goals with the recovered samples. The extraction began on September 21, 2004, and in January 2005, a first sample piece was sent for analysis to scientists at Washington University in St. Louis.

The first possible root cause of the failed deployment of the parachutes was announced in a press release a month after the crash landing. Lockheed Martin built the system with an acceleration sensor's internal mechanisms oriented wrong, and design reviews had not caught the mistake. On January 6, 2006, NASA investigation board chair Michael Ryschkewitsch revealed that Lockheed Martin skipped a pre-test procedure on the craft, and he noted that the test could have easily detected the problem.