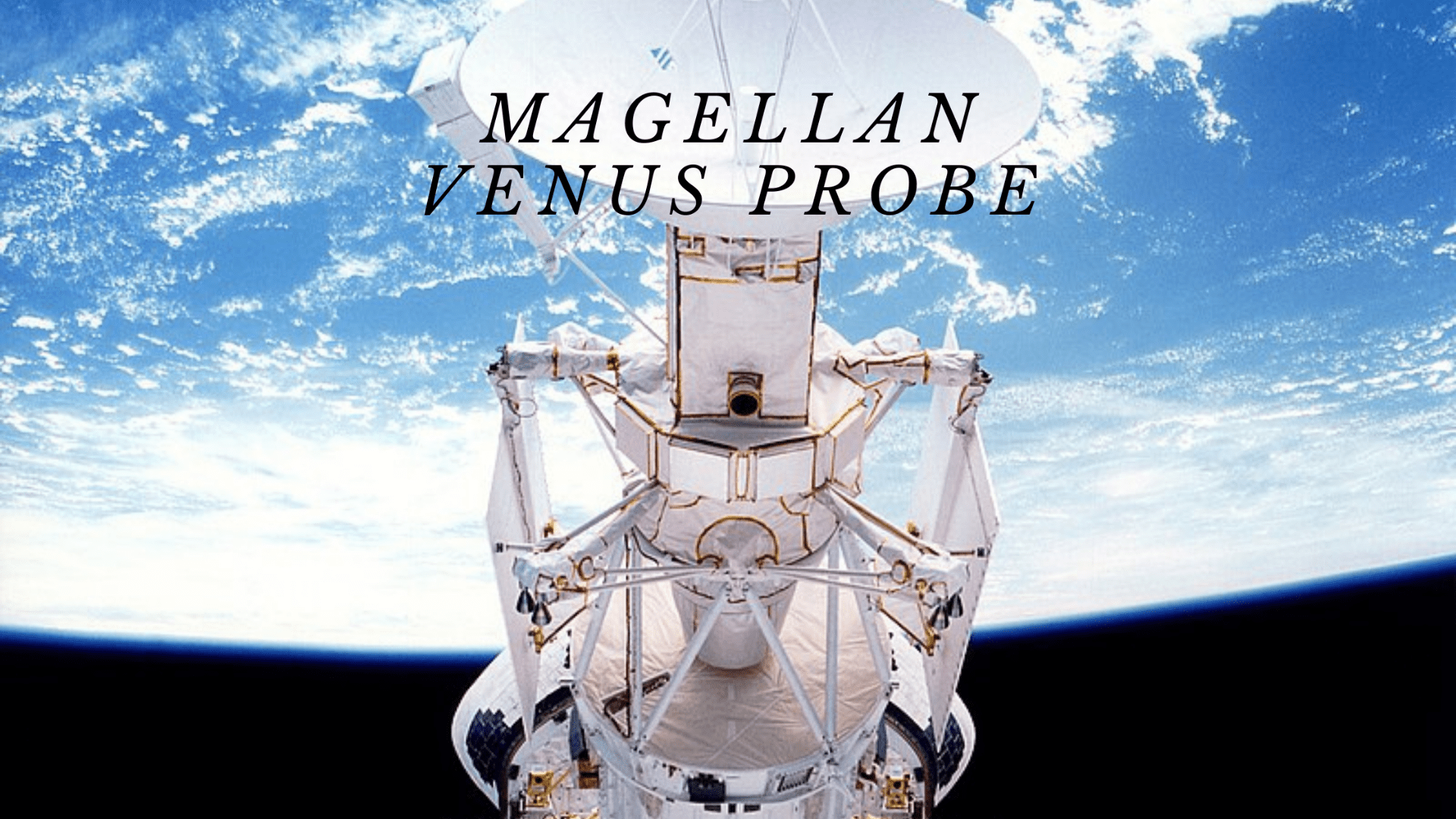

Magellan Venus Probe

The Magellan robotic space probe was launched on May 4, 1989, by NASA to map the surface of Venus and measure the gravitational field. Magellan was the first interplanetary mission launched from a Space Shuttle, the first to test aerobraking as a method for circularizing its orbit, and the first to use the Inertial Upper Stage booster. Magellan was the fifth successful mission NASA sent to Venus, and it ended an eleven-year gap in U.S. interplanetary probe launches.

The Space Shuttle Atlantis launched on May 4, 1989, carrying the Magellan spacecraft. Magellan and its Inertial Upper Stage booster were deployed from Atlantis while in orbit on May 5, 1989, which sent the spacecraft into a Type IV heliocentric orbit. It then circled the Sun 1.5 times before reaching Venus 15 months later, on August 10, 1990. Magellan had initially been scheduled for launch in 1988, but due to the Challenger disaster in 1986, several missions were deferred until September 1988. Magellan was also planned to be launched with a liquid-fueled Centaur G upper-stage booster, carried in the Space Shuttle's cargo bay. However, the Centaur G program was canceled after the Challenger disaster, and the Magellan probe was modified for the less-powerful Inertial Upper Stage.

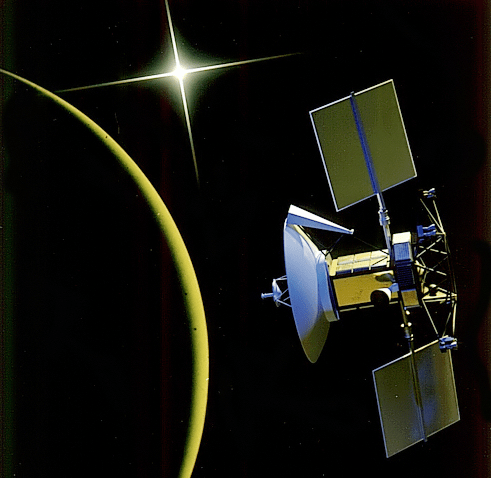

The Magellan high-resolution global images provide evidence to understand Venusian geology and the role of impacts, tectonics, and volcanism in the formation of Venusian surface structures. Volcanic materials mainly cover the surface of Venus, making volcanic surface features, such as small lava domes, large shield volcanoes, and lava plains, common. Additionally, there appear to be few impact craters on the surface, which suggests that the surface of Venus is less than 800 million years old, making it geologically young.

Magellan has successfully created the first and currently the best high-resolution, near-photographic quality radar mapping of the planet's surface features. Prior missions generated low-resolution radar globes with vague, continent-sized formations. However, Magellan has provided imaging and analysis of craters, ridges, hills, and other various geologic formations that are detailed enough to be comparable to the visible-light photographic mapping of other planets. Magellan's global radar map currently remains the most detailed Venus map in existence. However, the upcoming NASA VERITAS and Roskosmos Venera-D probes will carry much higher resolution radar equipment.

Magellan has successfully created the first and currently the best high-resolution, near-photographic quality radar mapping of the planet's surface features. Prior missions generated low-resolution radar globes with vague, continent-sized formations. However, Magellan has provided imaging and analysis of craters, ridges, hills, and other various geologic formations that are detailed enough to be comparable to the visible-light photographic mapping of other planets. Magellan's global radar map currently remains the most detailed Venus map in existence. However, the upcoming NASA VERITAS and Roskosmos Venera-D probes will carry much higher resolution radar equipment.

On September 9, 1994, it was announced in a press release that the Magellan mission would be terminated. Considering all the objectives had been accomplished, and due to the degradation of the power output from the solar arrays and onboard components, the mission was to end in October. In August 1994, the termination sequence began with a series of maneuvers that lowered the spacecraft into the Venusian atmosphere.

Communication was lost on October 13, 1994, at 10:05:00 UTC, when the spacecraft entered radio occultation behind Venus. The team continued to listen for another signal from the spacecraft for another eight hours when the mission was determined to have concluded. Although much of Magellan was expected to vaporize due to atmospheric stresses, some amount of wreckage is thought to have hit the surface by 20:00:00 UTC.